Ex-gangster writes book as part of mission to keep kids on the right path

‘Every child we ignore today is tomorrow’s gun-carrying, trigger-happy gangster’

(I first wrote about Farooque's book in the March 30, 2023 edition of The Progress – PJH, April 8, 2025)

Anyone who wants their child to be a doctor tells them to seek out medical training.

Want to be a lawyer? Write your LSAT and apply to law school.

But what if you want to teach your kids what not to be? Like a gangster.

On that subject mostly we hear from politicians or academics or the cops, but a member of organized crime who got out of the game is a rarity and is probably the only one with the real expertise to put the fear of gang life in your kids.

Meet Farooque Syed.

Syed used to be on a mission to get deals done, make money, stay out of jail, and stay alive. Now his mission is to make sure not a single kid follows the dangerous and reckless path he went down in life.

“I truly believe things happen for a reason, and me keeping you alive and out of prison and off the streets is what I feel I was sent to this Earth to do.”

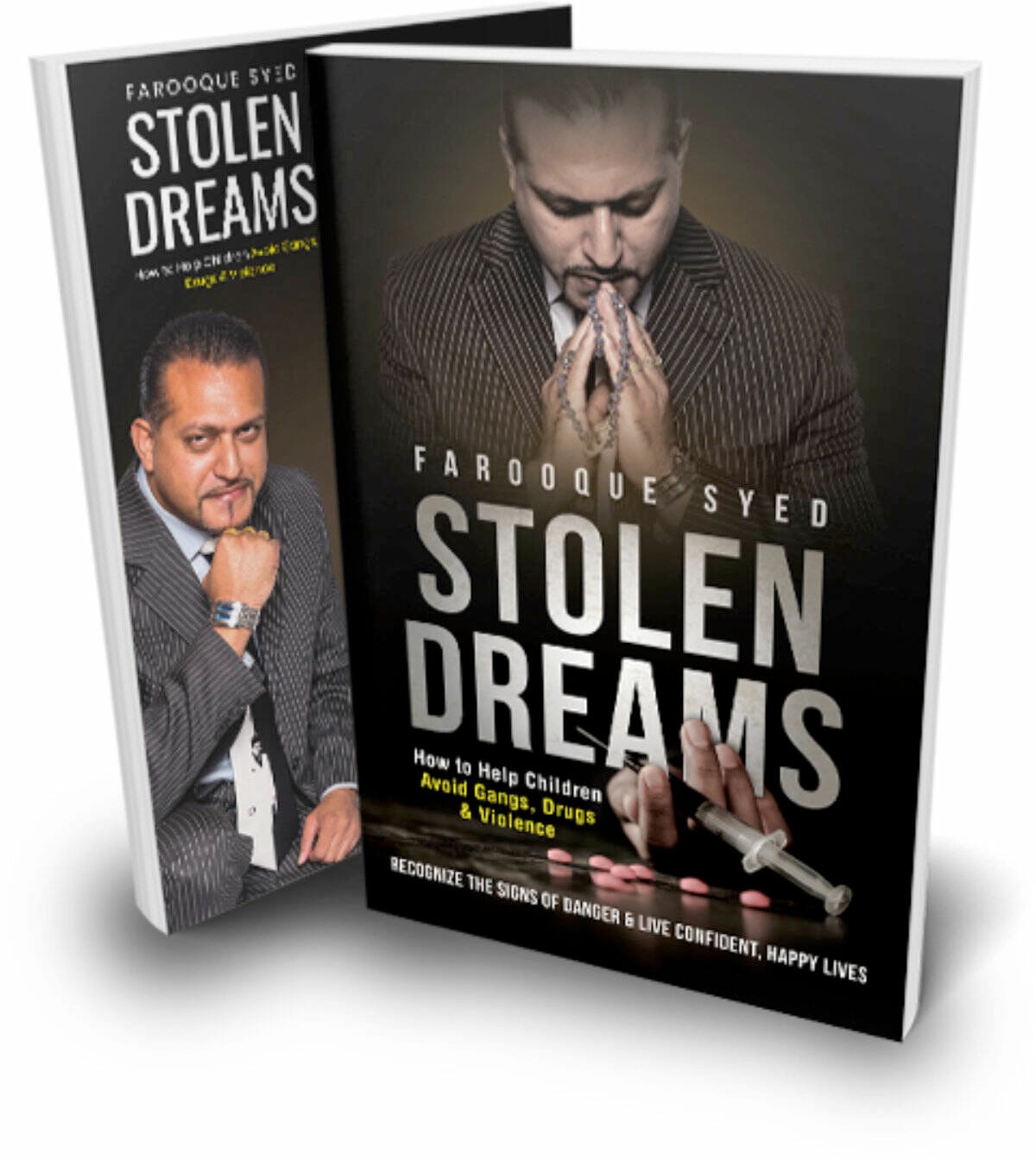

That’s from Stolen Dreams: How to Help Children Avoid Gangs, Drugs & Violence.

In Stolen Dreams, Syed lays out his childhood in South Vancouver and later East Vancouver as the youngest of five children in an upstanding, loving family. He was a good kid, did well in school, and he actually pursued a career in law enforcement. He started doing security as a stepping stone. But on the streets of South Vancouver as a teenager, he rant into childhood friends who were on a very different path.

“I got involved and recruited in gangs and organized crime without even realizing it in high school,” Syed said. “Later I was involved very heavily and moved up the ladder.”

His family came to Canada from Pakistan when Syed was just two. He discovered early on that the diversity and strength in South Vancouver was also something that created the foundation of South Asian gangs.

He writes in the book about the time he had his shiny new yellow bike stolen by two older white guys who called him a “lil Hindu boy.” He was shocked and in tears, but moments later two “powerful-looking” Indian guys went after them and retrieved his bike.

They took care of Syed.

“Due to racism and a neighbourhood that was truly diverse culturally, I was glad that we had this amazing camaraderie.”

But it was relationships like this that would lead to him into gang life. He made friends, forged alliances, often no different than cliques in high school. Eventually he was in a gang. At first he wasn't even doing anything illegal. Incrementally, that changed. He was given a pager by Mexican gang friends. Naively, he took packages and was told not to look inside, and he was paid hundreds of dollars to deliver them.

“It’s so subtle and easy to get these kids to mule, transport drugs guns, messages almost anything without them knowing,” Syed said.

Sometimes kids that may feel like nobodies are recruited to do small, street level stuff that makes them feel like somebody. Back in the 1990s, kids like him got into gangs almost by mistake.

Today things are different.

“Most will do it knowingly these days. The energy is different, the mindset is different now. Ruthless, dangerous, irresponsible, cut throat.”

After years in gangs, rising up to the level of someone who can make several calls to try to get a hold of kilograms of illegal drugs at a time, he was busted. He was convicted of importing three kilograms of heroin and sentenced to federal time, three years. He served almost two and a half years of that, but eventually was released. But unlike so many other repeat offenders and gang-connected dealers, Syed changed his ways.

Outside of prison, he was treated terribly by police, but he also realized that so-called friends in the gangs might not trust him anymore.

He saw heartbreak and turmoil. He saw drug deals gone wrong, friends shot to death. What he sees in today’s gang climate in the Lower Mainland is even worse. He says many of the gang-related shootings reported in the news aren’t even about serious money or drug issues.

What should be fist fights sometimes end in murder.

“These kids are killing each other for nothing,” Syed said. “Girl-related and disrespect feelings from over-inflated egos and ripping each other off.”

Stolen Dreams is easy to read, a work of non-fiction with a fiction quality because he changed all the names, many locations even, but he says it is based on his life without exaggeration.

“It took me 17 years to write and decide to publish my book,” he said. “Which I did not sensationalize at all. It’s written so any parent, guardian, educator, and elementary school child can read and learn.”

His passion today is prevention. Getting people out of gangs is nearly impossible, arguably futile, but preventing young people from going down that road is all that will help, he says.

“Every child we ignore today is tomorrow’s gun-carrying, trigger-happy gangster.”

Syed struggles today with Parkinson’s, a disease he has had for five years now, but he is still working hard to get his message out.

A few months after he published his book in 2022, he appeared at the West Coast Women’s Show in Abbotsford alongside Bif Naked as a speaker, and more and more schools and churches started to contact him to hear his story.

Stolen Dreams can be ordered through his website stolendreams.ca, which is also where anyone interested in hearing his message can get in touch.

-30-

Paul J. Henderson

pauljhenderson@gmail.com

facebook.com/PaulJHendersonJournalist

instagram.com/wordsarehard_pjh

x.com/PeeJayAitch

wordsarehard-pjh.bsky.social