Is the toxic drug crisis finally on the wane?

Chilliwack sees an anomalous drop in deaths from 2023

For nearly a decade we have been bombarded monthly with the numbers of people in British Columbia who overdosed and died.

On April 14, 2016, B.C.'s top doctor Dr. Perry Kendall declared a public health emergency that continues to this day, eight years and eight months later.

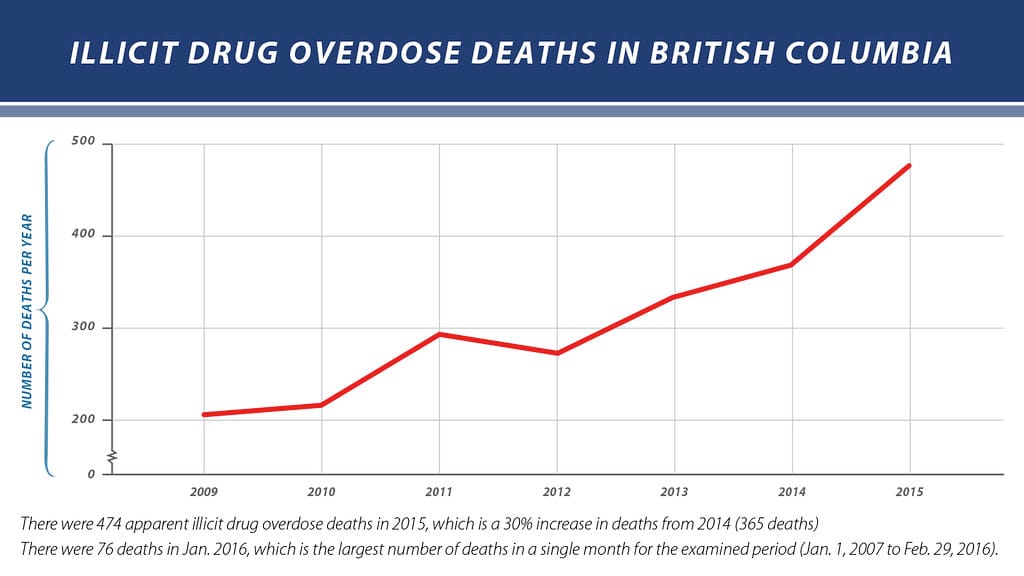

What triggered that declaration was a near tripling in drug deaths in just six years, from 2009 to 2015.

There were 474 "illicit drug overdose deaths"* in 2015, up 30 per cent over 2014. That number, 474, which triggered the declaration of the public health emergency more than quintupled in the subsequent eight years to 2023 when there were 2,574 deaths in the province. [*See below for more on the evolving language used in this crisis]

There was a steady rise in the numbers from 2009 to 2015 on to 2018 when the number hit 1,562. Things went from bad to worse as drug overdose deaths soon surpassed deaths by homicide, suicide or motor vehicle incidents combined. In 2019, however, there was a glimmer of hope that the crisis was coming under control as the number dropped to 991, the lowest since 2016.

So the timing of a global pandemic that through the world into an economic disaster and billions of human beings into states ranging from uncertainty to trauma. And the numbers started to shoot up again.

2020 • 1,776

2021 • 2,293

2022 • 2,382

2023 • 2,574

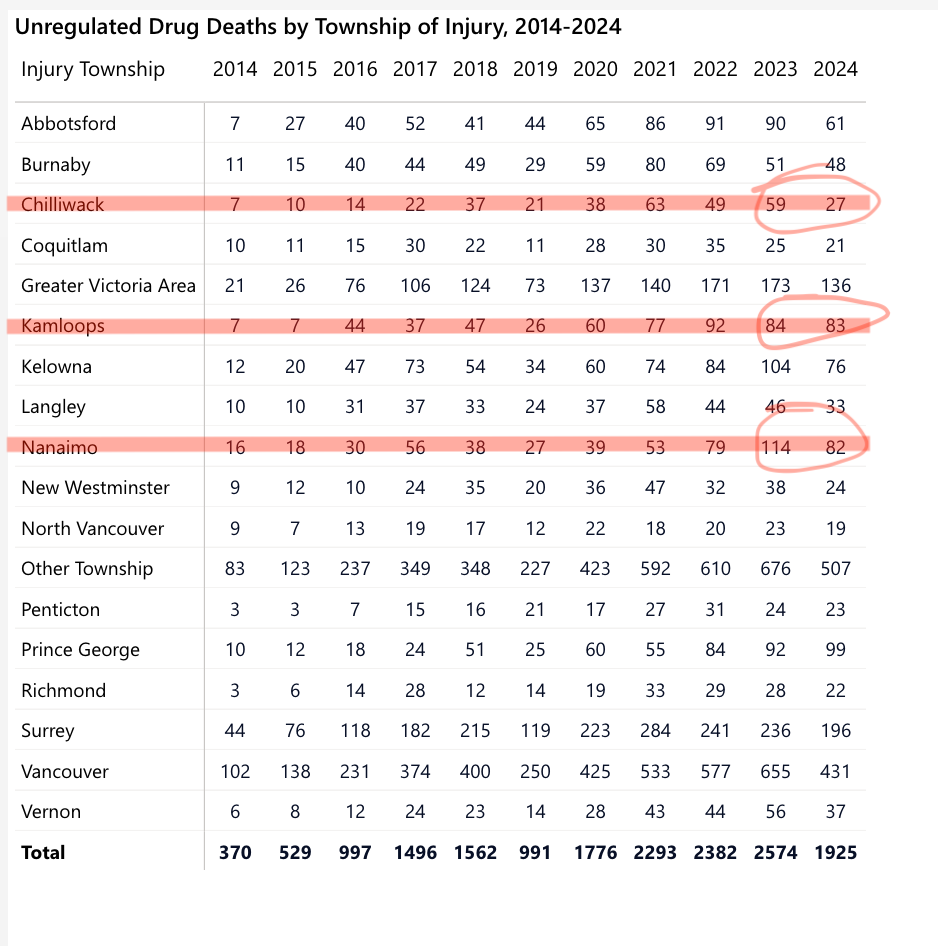

But is the crisis waning? It might be or it might be a blip. Up to the end of October 2024 there were 1,925 unregulated toxic drug deaths in B.C., which puts the province on pace for 2,310.

(Note: It is not beyond my recognition that we are dehumanizing the people dying by tallying them like widgets, and I am further dehumanizing them by extrapolating that 1,925 divided by 10 is 192.5 times 12 is 2,310. So there are 385 people likely dead or going to die in November and December of 2024. That is more than six people a day. Some of those people aren't even dead yet.)

The numbers point to a 10.3 per cent reduction in deaths in 2024 over 2023 throughout the province, which isn't exactly cause for celebration but might be a good sign.

More locally where I am writing from in Chilliwack things are particularly anomalous. What follows comes with the caveat that statisticians will tell you that the smaller the numbers you are dealing with, the harder it is to come to any substantive conclusions. For example, if there is one homicide in a community in one year and three the following year, saying there is a 200 per cent increase in the rate of homicide is accurate but is statistically silly.

That being said, there were 59 unregulated drug deaths in Chilliwack in 2023. As of the end of October there were 27, which puts the city on pace for approximately 33. That is a 45 per cent decrease year over year, a drop much lower than in similar sized communities.

The two cities I believe that are most useful for comparison based on population similarity and isolation, as in they. are not part of Metro Vancouver, are Nanaimo and Kamloops. Nanaimo is on pace for a 13.7 per cent decrease while Kamloops has already matched 2023 and is on pace for an. 18.7 per cent increase. Why the discrepancy? I can't say. Abbotsford is more than 50 per cent larger by population and their numbers are down 32 per cent. Langley by 28 per cent, so is it a Fraser Valley thing?

If we can find glimmers of good news in the statistics, it is noteworthy that no one under the age of 19 died in October due to unregulated drug toxicity. Back to the bad news, the rate of woman dying of drug toxicity is steadily on the rise.

Garth Mullins, who is a member of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users who has been commenting on the topic since I was in journalism school 25. years ago, who is also the host of the Crackdown podcast, said that the numbers do not indicate using drugs is safer now.

"I suppose the drug supply is very volatile, and that means it can have particularly bad months and months that aren't quite as bad," he told CBC News.

"That doesn't mean that the drugs that are going around right now are safe. Stuff you buy in the street is still very, very dangerous."

Language matters

Incidentally, as someone interested in words and language, and who worked as an editor with the Province's Government Communications and Public Engagement department, the terminology changed a few times. In 2018, the B.C. Coroners Service (BCCS) defined apparent illicit drug overdose deaths as "unintentional death involving street drugs and/or medications not prescribed to the person."

From a BCCS release from Sept. 27, 2018: "In British Columbia, unintentional illicit drug overdose deaths increased from 211 in 2010 to an estimated 1,450 in 2017."

Here have. "unintentional" and "overdose" in the same sentence, which seems redundant. If you were dosing your drugs, and you overdosed and died, obviously that was unintentional, right? Not if it was suicide.

But even "illicit" was not quite telling the story accurately, because most of these people were dying accidentally because they didn't "overdose" so to speak, they took drugs thinking it was one thing and it was something else. That's when we all learned about fentanyl, which was the toxic element in the mix killing people. Further complicating matters, we realized that fentanyl was killing people but not because it was toxic but because users didn't know it was in their benzos or methamphetimine or whatever they thought they injecting or smoking.

I wrote a column criticizing a local tow-truck driver who put a "Give 'em all fentanyl" sign on his pickup truck because not only was it insensitive, it was moronic because fentanyl is exactly what many of these street-entrenched hard drugs specifically wanted.

"I suspect “Give ‘em all fentanyl” is simply class war," I wrote of the one-time mayoral candidate's signage. "The sign looks like an attack on the poor, a finger-wagging moralism akin to the get-a-job mentality of those born on third base living their lives as if they hit a triple."

Now the language use is not "illicit" or even "overdose." The "illicit" suggests forbidden by law so I suppose why we don't use that anymore is because some of what people are overdosing on might be sold illegally but isn't an illegal substance. Take fentanyl even. Any woman who has had caesarian section birth likely had a dose of fentanyl. And "overdose" implies a person made a dosing mistake, which might be true but we don't like to blame the victim anymore.

From the government news release on Dec. 9, 2024: "Preliminary reporting released by the BC Coroners Service (BCCS) finds that 155 people died from unregulated toxic drugs in October 2024."

-30-

Paul J. Henderson

X@PeeJayAitch

Insta @wordsarehard_pjh

Bluesky @wordsarehard-pjh.bsky.social

Email pauljhenderson@gmail.com