Peeking behind the curtain: Canada's open court principle requires transparency but roadblocks are common

Noble words from Supreme Court of Canada, the Charter, but front-line reality can be different as some participants in criminal justice strive for opacity

Three messages I've received in recent days and weeks from people I won't name about three different stories, from pre-emptive insults to passive aggressive snark to litigious threats:

The vast majority of comments and messages I receive when writing about the courts are positive. Many are neutral or people asking questions, sometimes helping family members of victims or victims themselves navigate the not-at-all user-friendly system we have. But the oppositional and angry messages from people connected to offenders or from individuals who work in the criminal justice system are illustrative of how difficult it can be to engage in the simple democratic principle of telling the public about the workings of our courts.

What goes on in criminal courts in Canada often involves life-changing events for those involved, victims and offenders.

What goes on in criminal courts in Canada is also subject to the open court principle, an essential element in a democracy so that members of the public – either first hand or indirectly through the media – can theoretically see the workings of the system and determine whether or not justice is being done.

"Public access to court proceedings is an important principle in Canada," according to a brief statement on the Provincial Court of B.C.'s website. "Having members of the public attend provides public scrutiny, and ensures that our courts and judges are accountable."

Noble stuff, that is also affirmed in Supreme Court of Canada decisions and is there in black and white in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Specifically, section 2(b) of the Charter protecting "freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication." (Emphasis mine.)

As someone who has covered criminal and civil court, both provincial and BC Supreme Court, for 15-plus years, I can tell you that we have a pretty good system compared to the rest of the world.

But that's kind of a low bar. Not only is the system far from perfect by way of living up to the open court principle, there are actors within the system who sometimes actively work to thwart transparency.

The vast majority of people I watch and/or communicate with in courthouses are friendly and helpful, co-operative and transparent. The vast majority. But there are those who, consciously or not, serve to violate the open court principle in Canada every single day. From defence lawyers actively trying to thwart media coverage to the rare obtuse public prosecutor to occasional sheriffs or clerks who sometimes either aren't clear on what is allowed and legal and ethical, or they are similarly difficult.

Then there are the offenders themselves and family members who, for understandable if not good reasons, do not want their crimes and their court proceedings made public.

I've been threatened with several lawsuits over the years, almost always idle threats when people either get cold feet or realize they don't have a legal leg to stand on when it comes to Charter 2(b) rights. But a month ago I did get a threat of a defamation lawsuit from a lawyer who almost certainly knows better. I suppose he was happy to take his client's retainer to wield a flaccid Sword of Damocles over my head.

But offenders and their families make it difficult to report on criminal court for two obvious reasons: they have the most to lose, and some of them tend to be unscrupulous to begin with. They were charged with a crime after all.

I remember standing on the court steps at the Chilliwack Law Courts more than a decade ago talking to CBC court reporter Jason Proctor who was in town for the case of the hang-gliding pilot charged with criminal negligence after his passenger plunged to her death. A vehicle drove by and someone yelled out the passenger window: "Henderson you're a f—ing goof!"

Jason looked shocked. I laughed and said, "I'm pretty popular around here."

Then there were the two graffiti incidents. One was after I wrote about the trial of gangsters Curtis Vidal and Travis Soderstrom who were convicted of a violent home invasion in 2013. I had received some threatening sounding phone calls, vaguely claiming I was telling lies about the two in court by repeating what was said in court. Then one Saturday morning I woke up and saw the first of several messages letting me know about some fresh art work on the wall at the offices of The Chilliwack Times. It said "Paul Henderson is a child molester."

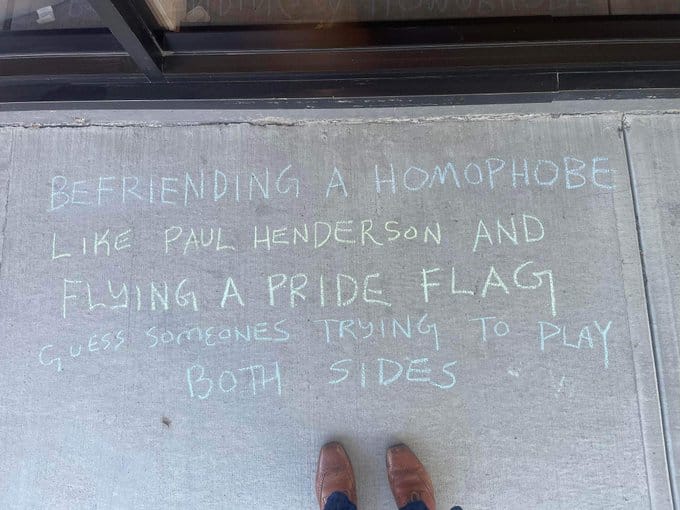

Years later at The Chillliwack Progress office one time the building was hit with, "Henderson goof." Then there was the chalk writing in front of The Bookman from a unfortunately mentally unstable fellow who fell prey to some conspiracy theories about UFV.

Last week it was a woman connected to the corrections officer (and/or his wife) convicted of smuggling drugs, phones and weapons into Kent Institution. She didn't seem to understand how the justice system or courtrooms or journalism work at all. Her pre-emptive anger in direct messages ordering me to not write about the case lest it hurt Lee's family were odd. She escalated wildly all the way to all-caps. So it had to be serious.

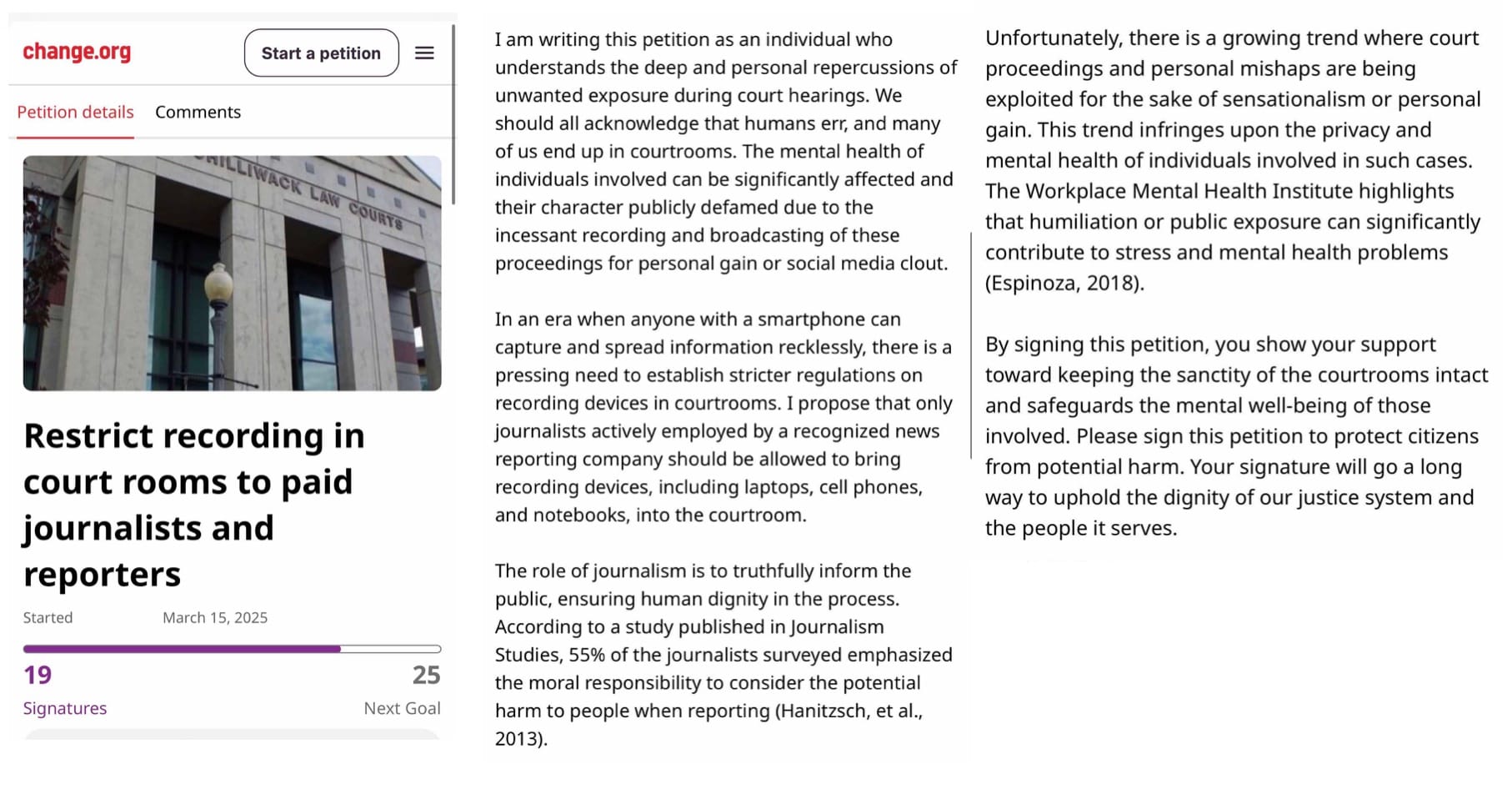

Then on Wednesday (March 19, 2025), someone shared with me a Change petition created by the wife of the corrections officer sentenced to five years prison for smuggling drugs and phones and weapons into Kent Institution as part of a conspiracy with gangsters. Jason Lee's wife suggested the information in the sentencing hearing should have been kept private, I guess. The factual and logical errors in the petition text are too many to get into, firstly that I recorded the hearing, which I am legally allowed to do but did not, secondly that reporting on serious criminal matters is somehow an attack on the mental health of people involved in court hearings.

At least this woman's outrage was borne of honest emotions and a desire to protect loved ones from shame or disgrace or notoriety. Ill-placed outrage but understandable.

All of these can be obstacles to court reporting and the open court principle but, not really.

It's the people who work in the system that really grind the gears of an open court principle to a halt.

Democracy's fathomable self-correcting mechanisms

One element of how historian Yuval Noah Harari distinguishes between dictatorship and democracy is fathomability of bureaucracy. The self-correcting elements of a democracy – voters, politicians, the media, and the justice system – need to be able to understand that which they are correcting.

"For a dictatorship, being unfathomable is helpful, because it protects the regime from accountability," Harari writes in his seminal 2024 book Nexus. "For a democracy, being unfathomable is deadly. If citizens, lawmakers, journalists, and judges cannot understand how the state's bureaucracy system works, they can no longer supervise it, and they lose trust in it."

The same applies to the citizens ensuring those self-correcting mechanisms themselves are fathomable, how elections are held, how the media is run, how the justice system operates.

On this latter element, the subject here, the Supreme Court of Canada is very clear in the "About us" section on its website.

"As a general rule, court proceedings are open and public. This is known as the open court principle and is protected by the right to freedom of expression guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. "

This was confirmed in the case of CBC v. Canada (Attorney General) in 2011: "The open court principle is of crucial importance in a democratic society. It ensures that citizens have access to the courts and can, as a result, comment on how the courts operate and on proceedings that take place in them. Public access to the courts also guarantees the integrity of judicial processes inasmuch as the transparency that flows from access ensures that justice is rendered in a manner that is not arbitrary, but is in accordance with the rule of law. (CBC v. Canada (Attorney General), 2011 SCC 2.)"

Somewhat ironically, this integral piece of SCC precedent was the first part of a decision against CBC and other media outlets who were fighting the ban on filming, photographing and conducting interviews in the public areas of courthouses. The media outlets also wanted to be able to broadcast the official audio recordings of court proceedings, something that is banned to this day in Canada.

Other than judges, the four most important roles who anyone who covers courts comes into contact with most commonly are defence lawyers, Crown counsel or public prosecutors, BC Sheriff Service deputies, and court clerks.

Defence lawyers

Lawyers defending accused offenders are professional and ethical and law-abiding, but of course are those with the most interest in protecting their clients.

The vast majority of defence counsel are OK with media coverage, co-operate or at least don't impede, some even seem to like it. I remember one time high-level drug dealers were at the Chilliwack Law Courts, Clayton Eheler and Matthew Thiessen, and both made cracks at me when they saw me.

It wasn't particularly intimidating but it felt highly inappropriate so I emailed both their lawyers to let them know of the sniping, just to see what they would say. Long-time gangster lawyer Ken Beatch ignored my email, unsurpringlly, but I was pleasantly surprised to hear back from Thiessen's lawyer who told me to tell him if it happened again, he'd drop Thiessen as a client.

But there are always incidents that are subtle with lawyers. Sometimes it involves a change in tone when they talk to a judge upon seeing me, sometimes I even get snide looks, sometimes passive aggressive reminders about publication bans and other court restrictions.

Just last week I went into a Supreme courtroom to sit down with my computer knowing there was a case up for sentencing, one I knew nothing about. I assumed it wasn't newsworthy but I sat in anyway because I had some time waiting for something else. The accused hadn't shown up but her brother and mother were there and a lawyer started talking with them. He wasn't acting as this defendant's lawyer but rather an amicus curiae, a friend of the court who helps a self-represented client.

He looked at me and said to them, "You should know this gentleman in the court is a journalist. He is going to write about this for his blog."

I stopped him, pointed out that I wasn't going to write about the case because it wasn't newsworthy. But the indirect, passive aggressive intimidation is not uncommon and not helpful.

Crown counsel

The lawyers who prosecute criminal cases are part of the B.C. government's public prosecution service. Usually referred to as Crown counsel, I have always had a good relationship with most of the ones I've come across.

Some were exceedingly helpful and friendly, making my job easier all the time. Others were civil and polite, only a couple surly ones. On the topic of the open court principle, I was in provincial court in Abbotsford recently and the Crown asked to speak outside the courtroom with a woman, a member of the community who had attended all the appearances and took copious notes. She told me that the Crown said he was worried she was passing on what was said in court to me when I wasn't there because some of what was said in court was repeated word for word in a story I wrote.

There was and is nothing wrong with this even if she did pass on notes and information to me. The public court principle means any member of the public can attend court, take notes, and do whatever they want with those notes, within reason. There are publication bans in several circumstances but generally what is shared at trial is fair game.

Intimidating a member of the public like this does nothing to deter me, but it does nothing to follow the open court principle and should not be something Crown ever does, in my opinion.

The only difference between myself and any other member of the public is that I have a card with my photo on it that is issued by the B.C. Sheriffs Service. This just means that I can type notes on my computer in the courtroom, I can record what happens for note-taking purposes, and I can post on social media, all things non-accredited people cannot do.

Sheriffs deputies

Deputies with the BC Sheriff Service work throughout the courthouse. They accompany remanded accused people to and from cells. They act as security and communication within the courtrooms. They sometimes manage court lists when they are long. They are the peace officers, the law enforcement in the courthouse.

I've never had a really bad experience with sheriffs and they are usually very helpful and reasonable. I did get asked for my accreditation card in a courtroom recently because I was on my computer, I gave him my card, he looked on his list and I wasn't on it.

I said, "Well you issued me the card so I should be on it."

He was interrupted by the judge and went so far as to agree there should be an adjournment while he discussed with her my accreditation. A silly waste of time that was soon resolved, but just another minor stumbling block to letting the public know what's happening in court.

Clerks

Court clerks work for the courts and essentially manage the courtroom dealing with the files, on computer and paper, and they tend to know what's happening.

Most of the clerks are great, but occasionally at the courthouse downstairs I go to ask questions about a file that I don't know something about. With a file number and/or a name, it isn't hard to look up a case and open it up. There does seem to be a very distinct fear of letting out more than they are allowed to. At times the clerks seem difficult, sometime asking me "why do you want to know?" and coming back with the bare bones forcing me to keep asking them to answer more questions.

I don't know if they are sometimes being belligerent or if they are just nervous about what they are allowed to share, I assume in all cases it's the latter.

The criminal justice system in Canada is public and open but for a few reasons, those listed above in addition to the challenge navigating the courts' websites. It isn't always easy, the road blocks are many, the obfuscation and intimidation is occasional, and it's all about as transparent as a fogged up window.

-30-

Paul J. Henderson

pauljhenderson@gmail.com

facebook.com/PaulJHendersonJournalist

instagram.com/wordsarehard_pjh

x.com/PeeJayAitch

wordsarehard-pjh.bsky.social